Growth hormone (GH) is a protein made by the pituitary gland and released into the blood in brief pulses. The major way that GH promotes growth is by increasing levels of the hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and its carrier protein, IGF binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3), in the blood. GH and IGF-1 work together on the cartilage cells of the growth plate in long bones to increase bone length leading to increased height.

Growth hormone deficiency (GHD) in children is defined as growth failure associated with inadequate growth hormone production. Growth failure should be evaluated in children whose length or height remains below the normal range (i.e. <3rd percentile) or whose length or height percentile is falling and is crossing major percentile landmarks over time. Before considering growth hormone deficiency as a possible diagnosis, a child with growth failure needs to be evaluated for more common conditions that can impact growth. Growth failure can occur in children who have inflammation (recurrent illnesses, arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, etc.), poor nutrition (inadequate intake or malabsorption conditions such as celiac disease, cystic fibrosis, etc.), other chronic conditions (psychosocial short stature, chronic renal insufficiency, liver disease, hypothyroidism, etc.) and genetic conditions that impact growth (skeletal dysplasias, familial short stature, Russell-Silver Syndrome, Turner Syndrome, etc.). Children receiving stimulant therapy for attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder may have impairment of growth, particularly if caloric intake is significantly affected. However, stimulant therapy does not cause GHD. Chronic glucocorticoid therapy (inhaled or oral) can cause significant growth failure. Children with constitutional delay of growth and puberty (“late-bloomers”) can have growth failure that may be difficult to separate from GHD.

Testing

Screening tests for GHD in children with growth failure with no identified cause include bone age X-ray and serum IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels. A delayed bone age is more common in children with GHD. An IGF-1 in the low part of the normal range or below normal increases the likelihood of GHD. An MRI picture of the brain showing a small or ectopic (misplaced) pituitary gland supports a diagnosis of GHD. The gold standard for diagnosing GHD is failure to increase GH levels in a growth hormone stimulation test (GHST). A GHST is performed in children after an overnight fast by giving a medication or medications (such as insulin, clonidine, arginine, glucagon, L-Dopa, etc.) to cause release of growth hormone into the blood and drawing blood frequently. If the highest growth hormone level obtained following two separate stimuli is less than 10 ng/mL, this is diagnostic of GHD. However, GHST is not required for diagnosis of GHD if other clinical parameters are present. Isolated congenital GHD may be associated with low blood sugars in infants and a small penis in male infants. Congenital GHD may be also be associated with multiple other pituitary deficiencies in infants and is increased in children with optic nerve hypoplasia and midline defects including cleft palate.

Diagnosis & Treatment

Children diagnosed with GHD benefit from GH replacement therapy with improved linear growth until the growth plates fuse. rhGH therapy is given by daily subcutaneous injections. Children and their families

are taught to self-inject rhGH at home. The rhGH starting dose is based upon the child’s weight and may be adjusted during therapy based upon weight gain, growth response and IGF-1 levels. Children receiving rhGH therapy should be seen by the pediatric endocrinologist every 3 to 6 months for monitoring of growth and adjustment of the rhGH dose. The earlier a child is diagnosed with GHD, the better the final height attained and the higher the likelihood that the child will reach a height that is normal for an adult. Some children with severe GHD will require rhGH therapy as adults due to the metabolic effects of GH.

How GH Affects the Body Other Than Growth

In addition to growth, growth hormone regulates the metabolism. As calories are consumed, growth hormone controls whether those calories are used to build bone, muscle and cartilage or stored as fat. Between meals, growth hormone regulates mobilization of fat for use as energy. Growth hormone deficiency is a condition that involves impaired linear growth and significant metabolic differences including changes in body composition (decreased bone mass, decreased lean mass and increased visceral adiposity) and lipid profile (elevated LDL cholesterol and triglycerides). In children with growth hormone deficiency, growth hormone replacement therapy is important to normalize the metabolism and maximize these metabolic benefits. If a child stops growth hormone prematurely, he/she will not be able to gain the benefits of maximal bone mineral accrual and lean body mass during his pubertal growth spurt and will have increased visceral adiposity and abnormal lipid profile; this can have a negative long-term impact on his/her bone and cardiovascular health.

Contributing Medical Specialist

Bradley S. Miller, MD, PhD

Professor

Pediatric Endocrinology

University of Minnesota Masonic Children’s Hospital

Minneapolis, MN

Medical Advisory Committee Member

The MAGIC Foundation

Psychological Impact of Short Stature on Children and Adolescents

Introduction

If you picked up this brochure, it is likely that you have concerns about the physical growth of someone close to you. Physical growth is often a sign of a child’s overall health. Given that growth is connected in many ways to health, it is important for children who are not growing at a rate considered within average range to be evaluated by medical personnel (1). For children who are extremely short compared to their same age peers, evaluation of height and possible related health issues is vital.

Unfortunately, we do not know much about the psycho-social impact of short stature on children and adolescents because little research has been conducted. We do know that short stature may place children at risk for bullying, social immaturity, and low self-esteem (2). Researchers have found that children with chronic illnesses/disabilities are at higher risk for school difficulties, anxiety, and depression (3, 4, 5). Children with growth delays often have related health conditions increasing their risk for social, emotional, academic issues.

Remember though, just because a child has a growth delay, does not mean they will experience emotional or psycho-social issues. Many children with growth delays seem to take their short stature in stride and progress through developmental milestones well within the expected age range. However, it is important that caregivers, physicians, and educators monitor the psychological, emotional, and physical well-being of children with growth delays.

Short Stature and Social-Emotional Development

Children who experience growth delays may be treated younger than their chronological age by peers, caregivers, educators, and others. Unfortunately, people often judge others by their appearance. People make assumptions based on how people look, how tall they are, and even how much they weigh. For many children with delayed growth, people associate height with age. When children are much shorter than their peers several things can happen. Adults and peers treat the child as younger which may interfere with psycho-social development. When behavioral and academic expectations are lowered based on height rather than chronological age, children may not learn the appropriate and expected behaviors for a child their age. Children often behave in a manner that is expected. If a child is treated as if they are younger than their chronological age, the child is likely to behave as a younger child would behave. If this pattern continues a child is likely to lag behind their peers in social, behavioral, and emotional maturity (6).

School Issues and Concerns

Most parents, regardless of their child’s growth, have questions about their child’s academic ability and achievement. Children with growth delays, much like children with other chronic conditions, appear to have variability in their academic achievement and school issues similar to the general population. However, several researchers have indicated that children with growth disorders, particularly those with co-occurring health issues or disabilities are at increased risk for academic difficulties and psychosocial issues (3, 4, 5, 7). Additionally, children who are significantly shorter than their peers may be an easy target for bullying. Parents and educators play a huge role in identifying possible academic difficulties including learning issues, attention issues, and social/emotional issues. If parents have any concerns about their child’s academics, intellectual abilities, physical or emotional health, social/relational development, or access to supports and services they should speak to their child’s school counselor, school nurse, teacher, or administration. The school has a responsibility for identifying children with learning needs and should follow up if the parents are concerned about their child. School counselors, teachers, and other personnel can be a tremendous source of support for children and their parents. If children are identified as struggling academically or behaviorally in school they will often be referred for further evaluation by a school psychologist or other professionals to identify learning, behavioral, or emotional issues.

Tips for Parents and Caregivers

Children often react to the emotions of their caregivers. Having a child with a significant medical condition can create stress and anxiety for parents, siblings, and extended family (8, 9, 10, 11). Parents and caregivers need to make sure they are practicing good self-care while at the same time providing the medical, health, social, and emotional support for their affected child as well as their other children. Siblings may experience stress, become worried and anxious, or may feel they must take on additional responsibilities to help ease the stress on their parents (11). Professionals recommend that parents pay attention to siblings’ emotional reactions and health as they have increased risk for depression and anxiety (11). Children with growth delays often face many medical tests and procedures which can be frightening and/or painful. Repeated hospitalizations due to tests, illnesses, medical procedures, or complications from a chronic medical condition can create chaos and stress for the entire family (10). Children, particularly young children, who experience repeated stressors or chaotic environments (i.e. hospitalizations, surgeries, repeated medical procedures) may be at increased risk for anxiety, depression, and stress related conditions (12). Finding ways to reduce stress for all family members is important.

Creating a supportive and nurturing environment while setting and maintaining boundaries is important for all children. When a child has a chronic medical condition or disability, special attention needs to be given to emotional and psychological health (10, 13). Below are tips for parents on how to create stable, nurturing, and supportive environments midst the chaos of chronic illness, medical testing, hospitalizations, and medication routines.

Create and stick to a routine as much as possible. Children are less stressed when they are in predictable environments with similar mealtimes, bath times, bed times, etc. Even when there is some kind of medical upheaval, it is helpful to try to maintain routines to the best of your ability (10). Adults can lower the stress by bringing along a favorite book, sleepy toy, pillow, etc. In addition, if you have the luxury of extended family or caregivers, it may help reduce sibling anxiety if children are able to stay in their own home and in their own bed while the affected child is in the hospital or traveling for medical treatment. Try to keep routines similar even when there are hospitalizations, medical treatments, or travel involved.

Develop or maintain a sense of humor. Humor can reduce tension and stress. Humor allows us to see the funny things that happen and can help us laugh at situations rather than treat them like they are the end of the world. Laughter is good medicine. Sometimes we need to learn not to take things so seriously. Pick your battles wisely and learn to laugh at absurdities.

Provide a supportive and safe environment but avoid becoming a helicopter parent. It is easy to become an overprotective parent when you have a child that is ill or can become ill or is injured easily. Put supports and safety measures in place, develop an emergency action plan to leave for babysitters and caregivers (even yourself), and create back up plan. Then, live life to the fullest. Allow kids to be kids and allow yourself, as a parent, to have time for respite, fun, and relaxation. We cannot prevent every illness, every sickness, every mistake, or every accident. If you bubble wrap your child you may unintentionally lower their self-esteem and resilience.

Be firm and consistent with discipline and boundaries. Even when children face challenges they need consistent discipline and boundaries. Consistent boundaries and rules help children know what to expect (10, 13). Over indulging children, spoiling them, and excusing their behaviors will not help them develop age appropriate behaviors that are so important in establishing and maintaining friendships. Learning to stay within boundaries helps children develop impulse control, learn interpersonal boundaries, and respect.

Learn to recognize typical verses atypical behavior. When parenting a child with a chronic illness or disability, parents are sometimes hyper alert to their behavior and development. While this can be helpful, it can also make us more prone to worrying about whether our child’s behavior is typical or not. There are great resources available to help guide you about when to become concerned about your child’s behavior based on their developmental level (10, 13). Remember, that you may have to “adjust” for age if your child was born prematurely or spent their first few weeks/months in the NICU.

Know when to be concerned and seek help. Most of the time, children with growth delays, their siblings, and their parents do just fine. However, having a child with a chronic medical condition puts extra stressors on everyone in the family and sometimes family members may need a little extra outside help (9, 13) . Below are some tips for when to seek help.

If the affected child or siblings:

· Experience unusually high levels of anxiety (9)

· Appear depressed, are overly sad for long periods of time, do not seem to enjoy things that once brought pleasure, withdraws from friends or activities (9, 13)

· Seem to feel guilty or overly responsible for the affected child’s health (9, 13)

· Acts out, seeks out attention inappropriately, or becomes disruptive (9)

· Threatens to harm self or others

· Gets into fights, throws things, or tries to harm self, others, or animals (9)

· Grades fall or the child demands perfection in all their school work and/or activities (13)

· Has meltdowns, lashes out in anger, or cries often over minor things

· Uses alcohol or drugs

· Seems to need coping skills or someone to talk to (9, 13)

· Other behaviors that persist and seem out of character that concern you

Counselors, clergy, school counselors, pediatricians, and other professionals can guide you in finding help for your affected child, siblings, and even yourself as the caregiver. Remember that emotional and psychological health impacts physical health. Continued stress can be harmful so make sure to seek help when needed.

Having a child with a growth delay or growth disorder can be challenging physically and emotionally (8, 10, 13). Parents and caregivers often feel stressed (8, 10, 14). and want to make sure they are doing all they can to ensure their child’s physical and emotional well-being. If you have questions or concerns about the growth of a child or how you can support and nurture a child with a growth delay or disorder contact MAGIC for information, resources, and support.

References

1. FloridaHealthFinder.gov (2018). Health Encyclopedia. Delayed Growth. Retrieved January 28, 2018. http://www.floridahealthfinder.gov/mobile/healthencyclopedia/health%20illustrated%20encyclopedia/1/003021.aspx

2. Cohen, P., Rogol, A.D., Deal, C.L., et al. (2008) Consensus Statement on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Children with Idiopathic Short Stature: A Summary of the Growth Hormone Research Society, the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society, and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology Workshop. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 93, 4210-4217. Retrieved February 5, 2018 from http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/jc.2008-0509

3. Pinquart, M. & Shen, Y. (2011). Anxiety in children with chronic illnesses: A meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica: Nurturing the Child, 100(8), 1069-1076. DOI: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02223.x

4. Pinquart, M. & Shen, Y. (2011). Behavior problems in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36(9), 1003-1016. DOI: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr042

5. Martinez, Y.J. & Ercikan, K. (2009). Chronic illness in Canadian children: What is the effect of childhood illness on academic achievement, anxiety, and emotional disorders. Child: Care, Health, and Development, 35 (3), 391-401. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00916.x

6. Stabler, B. Psychosocial issues of growth delay children. The MAGIC Foundation for Children’s Growth. Retrieved October 28, 2017 from https://www.magicfoundation.org/downloads/PsychosocialIssuesofGrowthDelayedChildren.pdf

7. Pinquart, M. & Shen, Y. (2011). Depressive symptoms in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36(4), 375-384. DOI: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq104

8. Holmes, A.M. & Deb, P. (2003). The Effect of Chronic Illness on the Psychological Health of Family Members. The Journal of Metal Health Policy and Economics, 6, 13-22.

9. Healthy Children.org (2015). Siblings of Children with Chronic Illness. Retrieved January 28, 2018 from http://www.healthychildren.org/English/health-issues/conditions/chroini/Pages/Siblings-of-Children-with-Chronic-Illnesses.aspx

10. Michigan Medicine. (2012). Your Child Development and Behavior Resources: A guide to information and support for parents. Children with Chronic Conditions. Retrieved January 28, 2018 from http://www.med.umich.edu/yourchild/topics/chronic.htm

11. Sharpe, D. & Rossiter, L. (2002). Siblings of children with chronic illness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(8), 699–710. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/27.8.699

12. Lerwick, J.L. (2013). Psychosocial implications of pediatric surgical hospitalization. Seminars in Pediatric Surgery, 22(3), 129-133.

13. Understanding Children and Chronic Illness: Protecting Your Child’s Emotional Health (2008). National Jewish Health. Retrieved January 28, 2018. https://www.nationaljewish.org/NJH/media/pdf/pdf-Understanding-ChildrenChronicIllness.pdf

14. Eker, L., & Tuzun, S. H. (2004). An evaluation of quality of life of mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation, 26, 1354-1359. Doi: 10.1080/09638280400000187

Yvette Q. Getch, Ph.D., CRC

Associate Professor and

Coordinator, Graduate Counseling Programs

Dept. of Counseling and Instructional Sciences

University of South Alabama

Mobile, AL

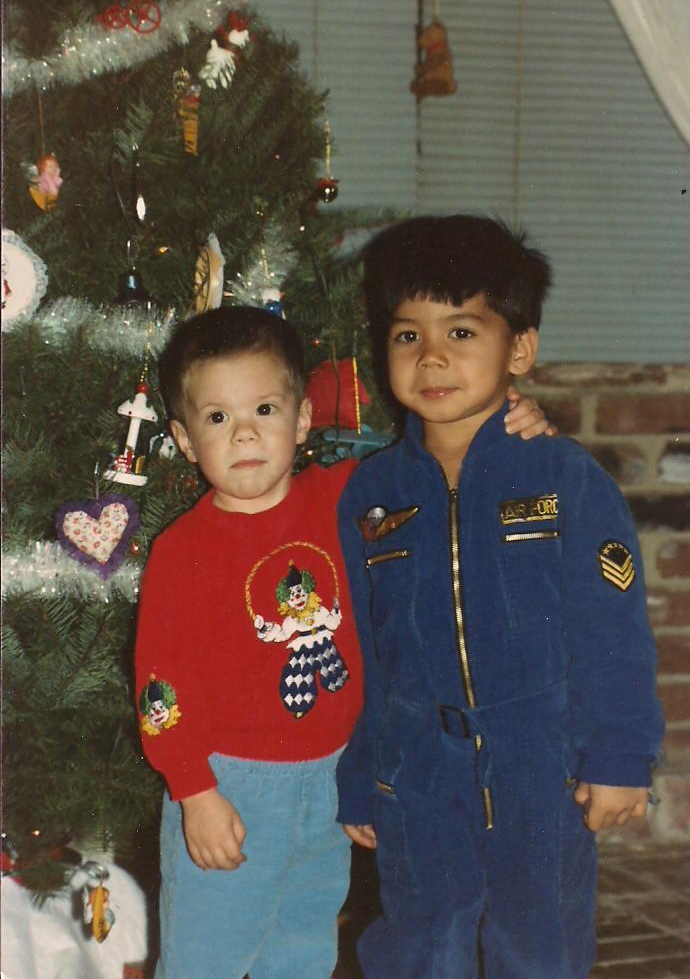

Courtney's Story

My name is Courtney Rivard. My MAGIC story is slightly different than most people’s beginning. In 1985, when I was three years old, my younger sister and I stood eye to eye. We are a year and a half apart, and it caused my parents’ concern. They began questioning my health, and after a few years of stress, at the age of five, a pediatric endocrinologist diagnosed me with Hypothyroidism and Growth Hormone Deficiency and started me on therapy. I was one of the first kids in the country in the study for bioidentical growth hormone therapy. (You can see our long family struggle for diagnosis here: https://www.magicfoundation.org/jamie-harvey/ )

Fast forward to the year 2012. By this time, I am happily married and have 2 amazing sons. They are 14 months apart in age, and because of my medical history, in addition to their regular pediatrician, we also had a pediatric endocrinologist follow their growth. At the age of 8, my youngest son was diagnosed with growth failure and began therapy. One year later, my oldest son was also diagnosed with growth failure.

Today, in 2022, they are 17 and 18 years old. We are so happy that they are both healthy and thriving. They both stand about 5’9 which is spot on for where they should be. They often argue about who’s the tallest, and I just giggle. They are both healthier than they would have been if we had not had the opportunity of growth hormone therapy. My medical history made the choice to put them on therapy simple, and for this, I am lucky.

As an adult, I am considered adult growth hormone deficient. We are a military family and have had to move often, so finding an endocrinologist who has managed adult growth hormone deficient patients has been difficult. I am currently not on treatment. This is a challenge I will continue to face until we finally settle into a home base with medical services near us. But in the meantime, my new journey with MAGIC in a different role begins.

The people who laid the groundwork of MAGIC have created a support system like no other. I am so proud to have been a part of it as a child, a mom of affected children, and now working to help support other families. I know from personal experience how valuable a team of parents and patients can be and I cannot wait to see what the future holds for MAGIC. Please feel free to contact me at courtney@magicfoundation.org and share your stories. I would love to hear from you.

Resources

» Download a printable version of the GHD brochure

» Download a printable version of the Dental Problems Associated with Growth Hormone Deficiency brochure

» Click here for dental clinical article: Occlusal Characteristics of Individuals with GHD, ISS and RSS

» Download a printable version of the Psychosocial Impact of Short Stature on Children and Adolescents

» Download a printable version of the Frequently Asked Questions when Beginning Growth Hormone Therapy brochure

» Click here for member benefits or to join The MAGIC Foundation

» "LIKE" The MAGIC Foundation's Facebook page

» Join our closed GHD Facebook group for parents. After you request to join, please message an admin to gain access or email Courtney at courtney@magicfoundation.org

» Jamie's Story - A Mother's Journey about her Growth Hormone Deficient child

» Would you like to speak to someone about GHD? If so, call The MAGIC Foundation at 800-3MAGIC3 or (630) 836-8200 or Email Us

Clinical Trial Information

Power is the only place on the internet where patients can access clinical trials directly. We help more patients find treatments and speed up the process of medical science as we go. We are a small team - each of us with our own personal story and motivation to make a difference in the lives of patients and advance Power's mission.

For assistance outside North America, visit our International Coalition to see resources in your country